The origin of these creatures is however a quite different story to tell.

Now, there’s nothing to suggest that the existence of trolls in the folk tradition implies a belief in actual, fleshly creatures with cascades of gold hidden deep within the mountains, as in the fairytales. These creatures belonged purely to the imagination, and had more or less a pure entertainment feature, which perhaps is best pinpointed in the descriptions of their appearance; awfully ugly they are, often with only one eye, covered with hair and with grotesquely large noses.

Meanwhile, tales and legends tell us that the troll is in a continual battle with humans and all the great powers of the world, a battle that should also be interpreted as a symbolic such between man and nature - the dangers one might have to face, if daring to move from the safe infields and out into the unpredictable outlying areas where the subterraneans subsided. By linking dangerous spirits to the wilderness, these legends as well as the folktales communicate a quite gloomy perception of Mother Nature, and refer to it often in relation to darkness, fear, loneliness, storms, hardships and enormous distances. In turn, stories about trolls (also referred to as jotun or jutul) originated as explanations of natural phenomena’s that bore witness of tremendous power and strength; legends about giant canyons and rocks, deep valleys and narrow gorges might in this sense be interpreted as primitive myths of creation. A legend from Telemark explains that

On Håkåneset – the mountain at Tinnsjø, stood a jutul, peering over to Nummedal, hoping to get across. But not matter how he tried to make his way forth, he always seemed to stumble, and he slipped on his heel down the vertical rock wall. Today, a furrow in the mountain appears from top to bottom, telling the tale of the giants’ clumsiness.Also around Dovrefjell - a mountain range in central Norway -, a number of stories have existed and been told, referring to the mountain as the home of the jutuls. Even King Harald Fairhair – the first king of Norway – had, according to the legends, grown up in these wild mountain tracts, and been fostered by a giant. Also stories associated with Jutulporten (eng. “the giants’ gate”) in Vågå and Jutulhogget (eng. “the giants’ chop”) in Rendalen, bear proof of a vivid understanding of the powerful forces which had been at work, exceeding any human force, or any known natural law. Trolls can thus be understood as a generic term for all kinds of beings and phenomenons threatening human existence.

|

| Gerd and Frey, wooden freeze by Dagfin Werenskiold (1892-1977), in the courtyard of Oslo City Hall. Photo by Camilla Christensen, June 2016 |

Many giants are also in possession of great wisdom, such as Vavtrudne (Vafþrúðnir), who battles non other than Odin himself, in finding out which is most clever. It is however the battle between the giants and Thor, their most dangerous opponent among the Aesir, which is a main subject in the Norse myths. "The mountain troll roared, thundering in the mountains, the entire ancient earth was shaking," we are told in Hymeskvadet (eng. Hymir's poem). “Waking up the trolls" was therefore considered a major crime in the oldest Norwegian laws.

|

| Tor's Fight with the Giants (1872), depicted by Swedish artist Mårten Eskil Winge (1825-1896) |

The trolls we meet in legends, fairy tales and folk songs actually have a lot in common with these mythological giants, who lived in enmity with gods and humans. But while the fairytale trolls live in what the French folklorist Virginie Amilien has described as "the other world" – the fairytale world, East of the Sun and West of the Moon - these giants inhabited the realm of men; far away, but still within our borders. For ages, these creatures have been a part of Norwegian folklore, and in the sagas, the troll is a dangerous and frightening antagonist with magical powers. It can only be defeated by Christian truth, after which it will return to the mountains – traditionally pictured as a leader of the Christianization of Norway, King Olaf II Haraldsson (also known as St. Olaf), is widely portrayed as a trollslayer. Many churches were built in his name, churches the trolls tried to destroy by throwing rocks at them. It proved, however, that Olaf was a force to be reckoned with, and threw the rocks in return. As a result, many local legends tell stories about mysterious holes in the landscape, bearing witness of the combat. Such stories tell us that it previously was a connection between the trolls, humans and gods. Olaf, in this sense, emerges almost like a personified force of nature, as with the trolls he's fighting against.

In the long run however, the implementation of Christianity had a strong influence on the ancient Norse conceptions of the trolls. In early Christian sources, the troll is associated with the devil, the main enemy, but later iconographic representations give them a quite different and less frightening look. Disparagement was thus one of the main ways that the Christians used to devaluate the value of the elderly and pagan beliefs. Although retaining their status as man’s antagonist, the troll was robbed of much of its former authority. While their ancestors in the ancient saga writings was characterized as powerful beings to be reckoned with, the fairytale trolls were driven farther and farther away from the human sphere. The dangerous and powerful mountain troll that is depicted in the Poetic Edda, was to a great extent weakened and portrayed more as harmless and low-brow beings, made easy to fool by heroes such as the Ashlad.

|

| "If you do not keep quiet," he shouted to the troll, “then I'll squeeze you like I squeeze the water out of this white stone!" Illustration by Theodor Kittelsen |

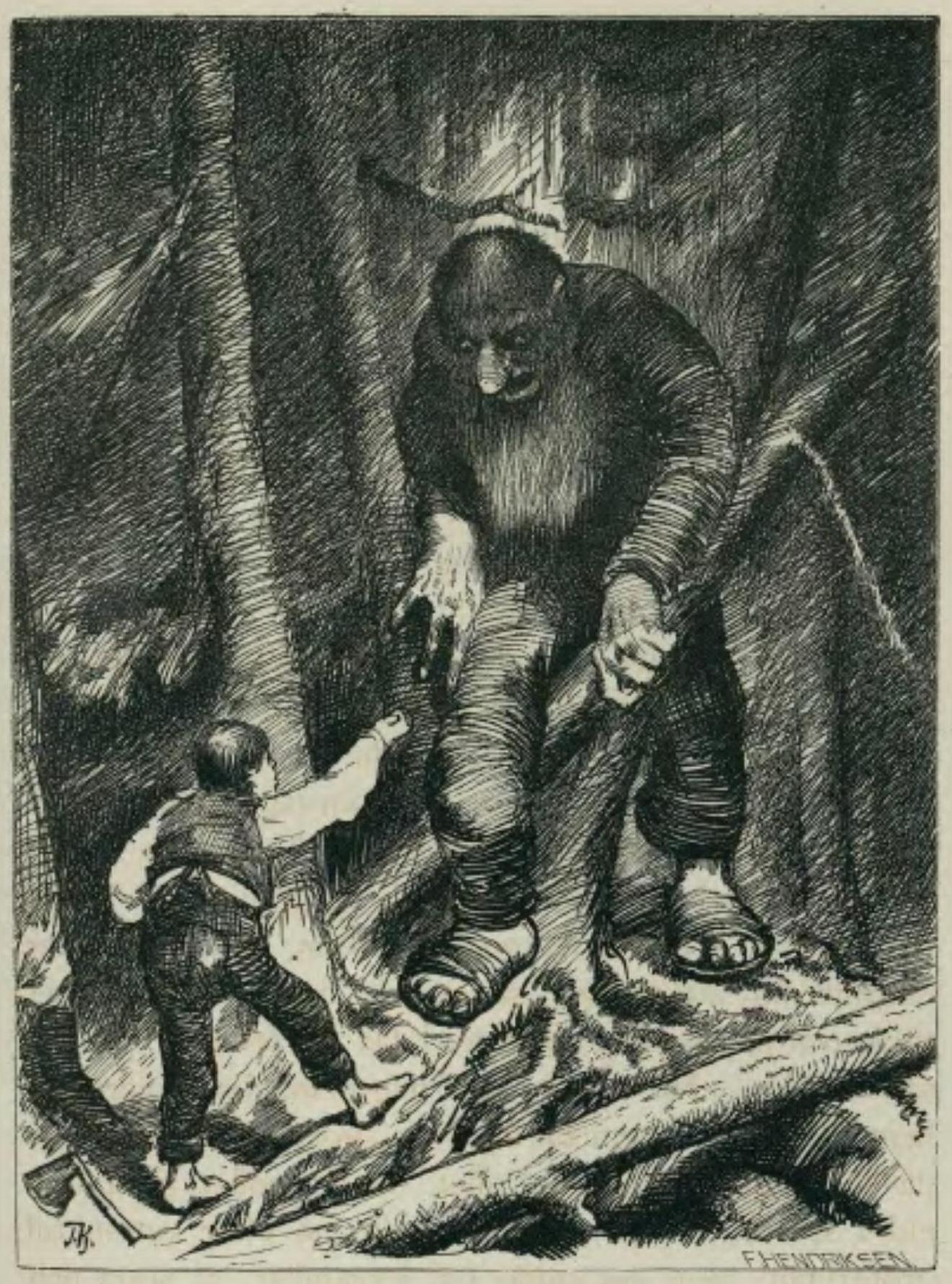

In a fairytale called The Gold Bird, a bird of gold steals apples from the king's garden, and loses a feather during the misdeed. The King's youngest son travels out to find the villain, and bring back the apples. On his journey he meets a fox who helps him through the trials he is exposed to along the way – among these are three irate trolls. In the illustration of this fairytale, artist Theodor Kittelsen chose to portray a highlight in the text that tells of the meeting between the trolls and our hero – in this case, when the fox helps the prince out of a troublesome predicament. He has in fact something that belongs to the trolls, and so the fox disguises himself to mislead them:

"Have you seen someone passing by with a beautiful, young maiden, a horse with golden bridle, a golden bird, and a gilded linden tree?" they shouted.

"Yes, I have heard from my grandmother's grandmother that such a journey has taken place; but it was in the good old days, when my grandmother's grandmother baked penny pies and took two for a penny."

Then all the trolls laughed with their mouths wide open. "Ha, ha, ha, ha! If we have we slept that long, we might as well go back to bed," they said, and then they turned and went back the same way they came from.And how does a troll actually laugh? Little information is communicated through the fairytale, if any. We know that they “squirt fire" when they are angry, that they are burly and crude, large, violent and ugly. Kittelsen therefore believed that their laughter had to be likewise; although the inspiration for the illustration was based on the fairy tales and folk belief, there was also room for a great deal of his own personal imagination. Thus, Kittelsen had to make several revisions along the way, as the first drafts were characterized by a more gruesome approach. At the request of publisher Peter Christen Asbjørnsen – who believed that the children would be frightened – the terrifying trolls from the first drafts were toned down. Instead, they were to a greater extent depicted as more harmless and humanlike beings; the laughter became in this sense a way to defuse the trolls.

This illustration is a good example of the more modern “tell tale” tradition, depicting trolls as dangerous, but rather dumb, fully possible to overcome with the use of wits and common sense. Although they have passed on the old notions of multifaceted, ghoulish creatures which could not stand the light of day, the actual fear of them was increasingly diminishing as their domain to a greater extent were confined to fantasy and fiction, hence losing its grounding in the popular folk belief.

Nevertheless, it is tempting to say that through the legends, we still have the possibility to understand the former primal force of the Norse giants - the implacable opponents of Odin, Thor and the other aesir. The remarkable rock formations that are often found in places where nature is particularly unbridled have often acquired their names reminiscent of the temperament of the trolls; for people passing through, these names were a reminder that they were in a wild and dangerous landscape, demanding vigilance and caution. In this perspective, essence of the trolls remained close at hand to make the journey unsafe, bearing witness of their original authority. Trolls in mythology, fairy tales and legends can therefore be regarded as evidence of our ancestors’ vivid encounters with Mother Nature –perhaps as products of the imagination, but nonetheless an indicator of a long lost reality and truth.

|

| He shook the earth to its' very core. Painting, oil on canvas. Theodor Kittelsen (1900) |

Sources:

- Amilien, Virginie. "Troll and other Supernatural Creatures in Norwegian Folktales". I Norveg – tidsskrift for folkloristikk. Årgang 39. Nr. 1. 1996.

- Amilien, Virginie. "Den annen verden i norske folkeeventyr". I Nord-Nytt – nordisk tidsskrift for folkelivsforskning. Nr. 65. 1996

- Bø, Olav og Hodne, Ørnulf. Norsk natur i folketru og segn. Det norske samlaget. Oslo 1974.

- Bø, Olav. Trollmakter og godvette. Det norske samlaget. Oslo 1987.

- Christensen, Camilla. Og skogen gav os eventyret: møter mellom ånd, natur og folketro i Theodor Kittelsens kunst. Masteroppgave ved Universitetet i Oslo, 2011. URL: https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/24298/Master.xCamilla.xNyttxdokument..pdf?sequence=4

- Edda-dikt. Oversatt av Ludvig Holm-Olsen. J.W. Cappelens Forlag. 2. reviderte opplag. 1993.

- Hodne, Ørnulf. Det gåtefulle Norge. Mystiske steder. Sagn. Folketro. J.W. Cappelens Forlag A.S. 2004

- Hodne, Ørnulf. Vetter og skrømt i norsk folketro. J.W. Cappelens Forlag. 1995

- Hodne, Ørnulf. Det norske folkeeventyret. Fra folkediktning til nasjonalkultur. J.W. Cappelens Forlag A.S. 1998

- Koefoed, Holger; Økland, Einar. Th. Kittelsen. Kjente og ukjente sider ved kunstneren. J.M. Stenersens Forlag A.S. 1999.

- Landstad, M.B. Mytiske sagn fra Telemarken. Efterladte optegnelser. Oslo (Norsk Folkeminnelag) 1926.

- Myrvoll, Klaus Johan. "Jotun". (2015, 4. mai). I Store norske leksikon. Hentet 10. mai 2016 fra https://snl.no/jotun.

- Norsk Folkeminnesamling. Gullfuglen. AT550. Samler: P. Chr. Asbjørnsen. Sted: Sel, Oppland. År: 1842

Smoke Weed Everyday!

ReplyDeleteThank you, thank you for these information!

ReplyDeleteThis blog is gold mine :)